Dressage riders who want to compete in higher classes will sooner or later have to deal with the subject of the double bridle, as the double bridle becomes compulsory in most competitions from medium level upwards.

The following article is intended to provide guidance on how to choose, fit, and use a double bridle correctly and in a horse-friendly manner in order to ensure a content horse and fine control of the rider's aids.

Basically, everyone can decide for themselves whether they want to ride with a double bridle. If you decide to use a weymouth bit, you should have completed the training up to a certain maturity. The weymouth is an aid for refining the aids, but at the same time it also serves to test the rider's abilities and requires the following skills from both rider and horse:

- Balanced and relaxed seat, independent of the hand

- Soft rider's hand, even and coordinated impact

- Interaction of the aids should function

- Content and calm contact with the snaffle bit

- Balanced horse that does not lean on the reins

- Good reaction to and acceptance of weight, leg and rein aids

- The horse should already show willingness to collection, have developed basic self-carriage and impulsion

Many of you already know how a double bridle is constructed. However, for the sake of completeness (and because the basic technical understanding is so important!), here is another rather brief description.

In dressage, the weymouth is always used in combination with a snaffle (or bradoon). It is used with two pairs of reins and a steady connection, whereby the rein aids are primarily given via the bradoon. The curb rein is only used to refine the aids.

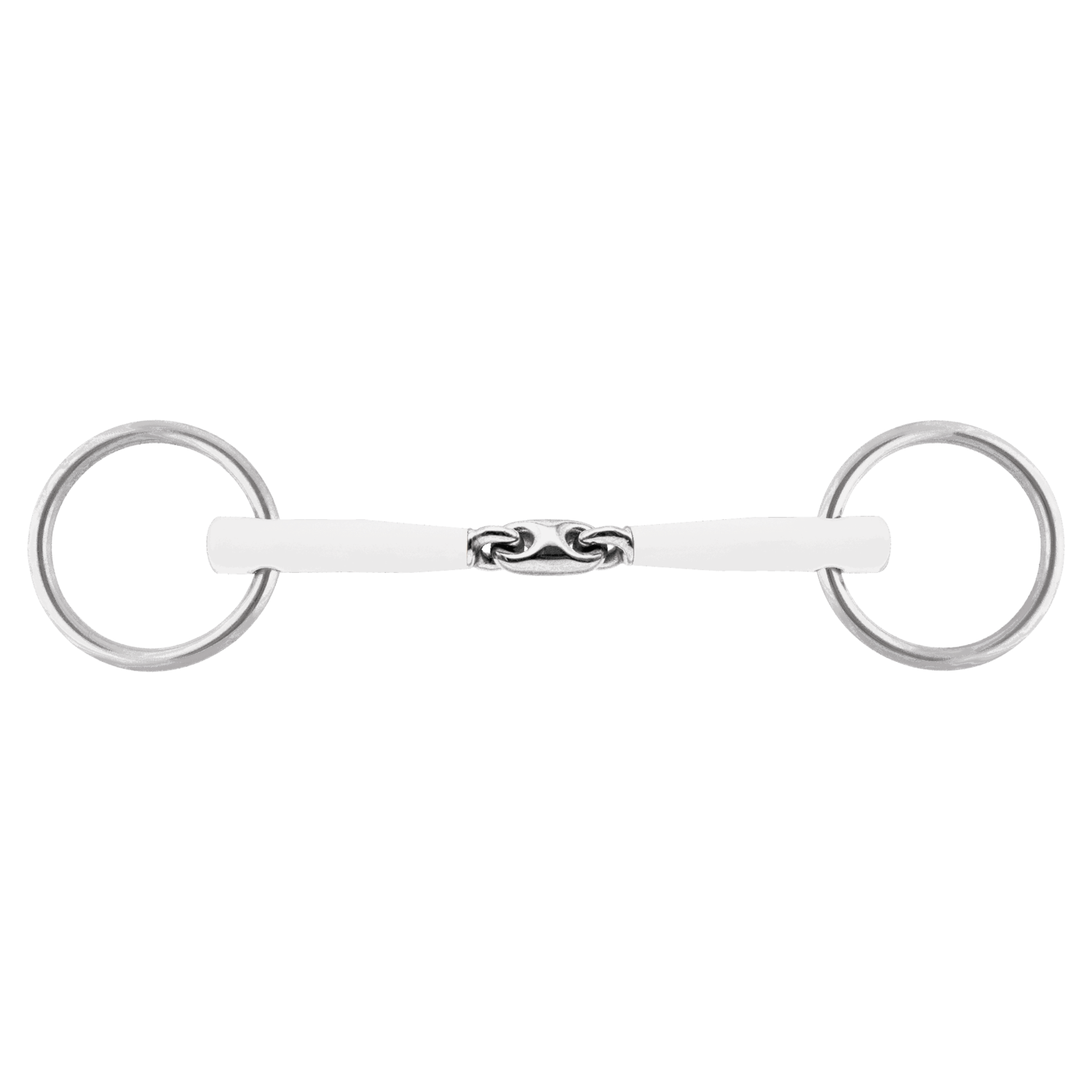

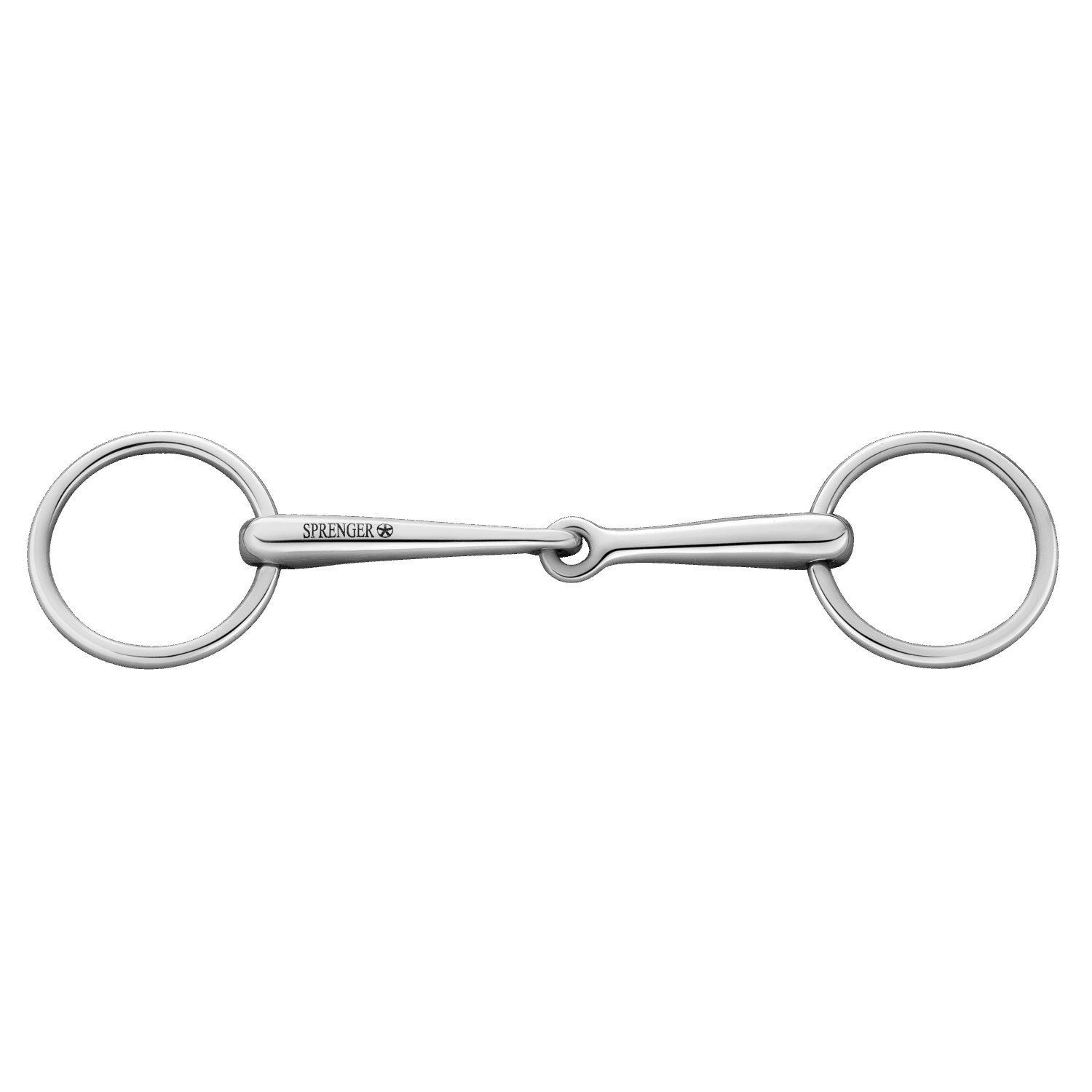

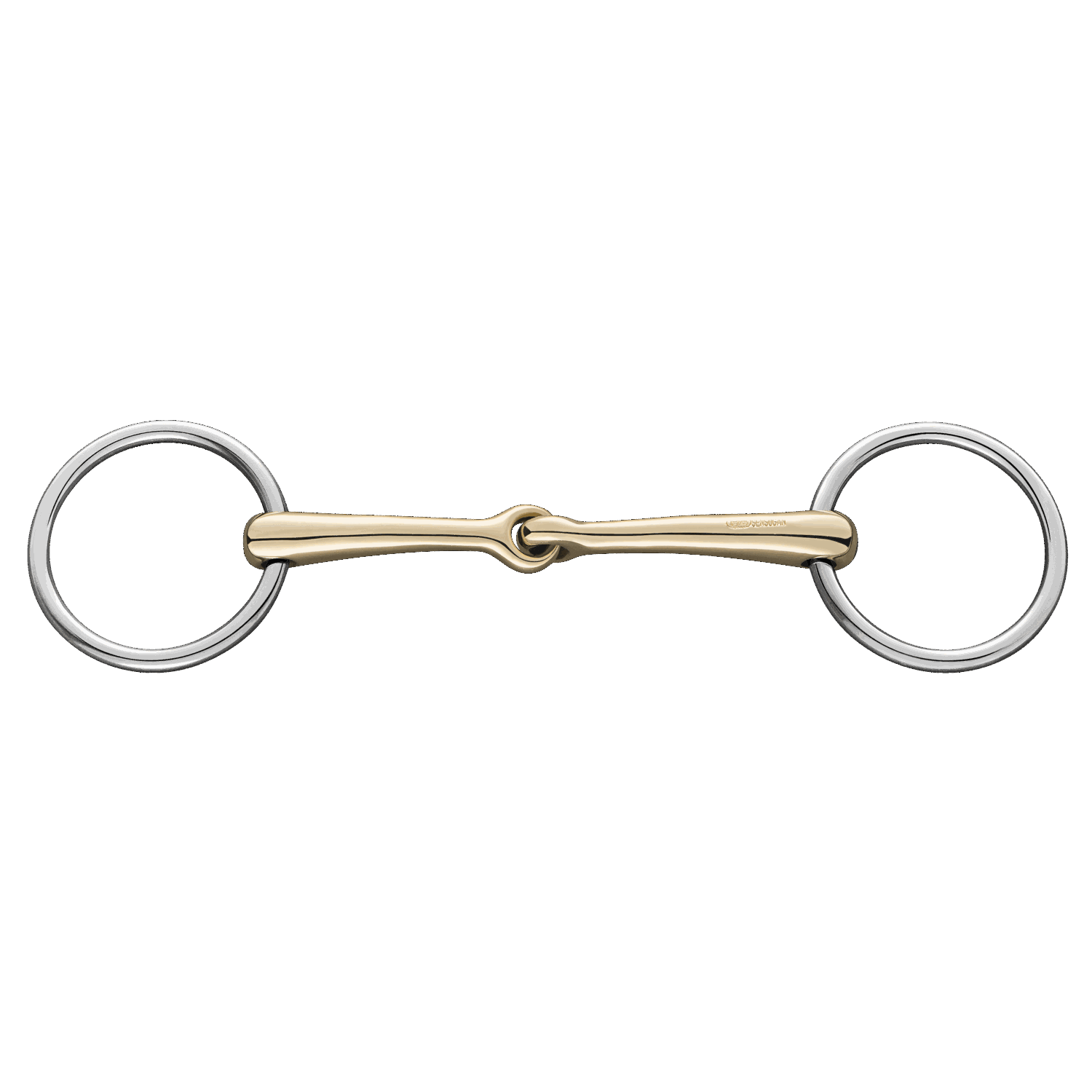

The bradoon has a single or double jointed mouthpiece and is used with the main rein. The rider impacts the horse's mouth with the tongue. The effect is the same as that of a normal snaffle. In our blog article 'How do I find the right bit?' you can find more information about the different types of bits and their effect.

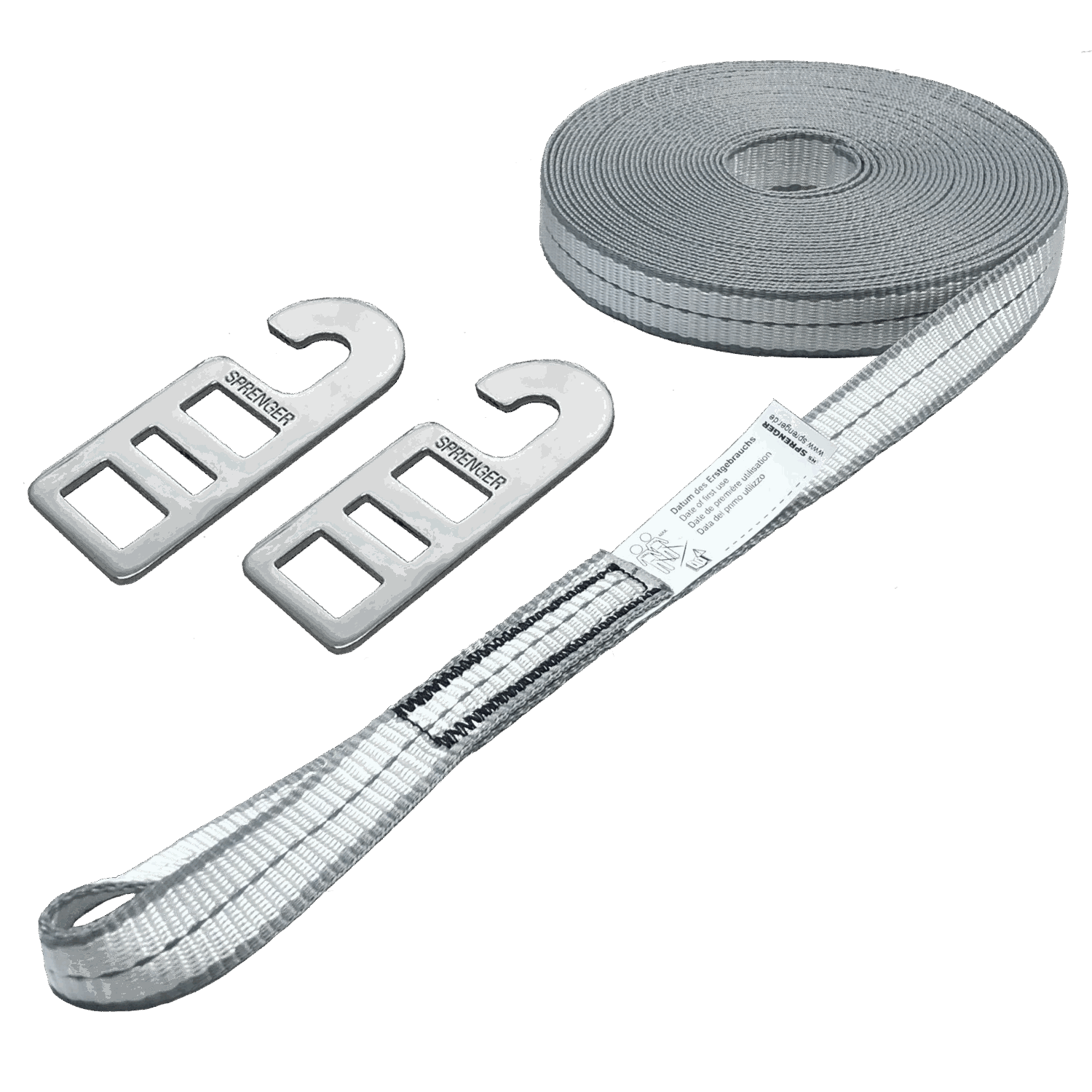

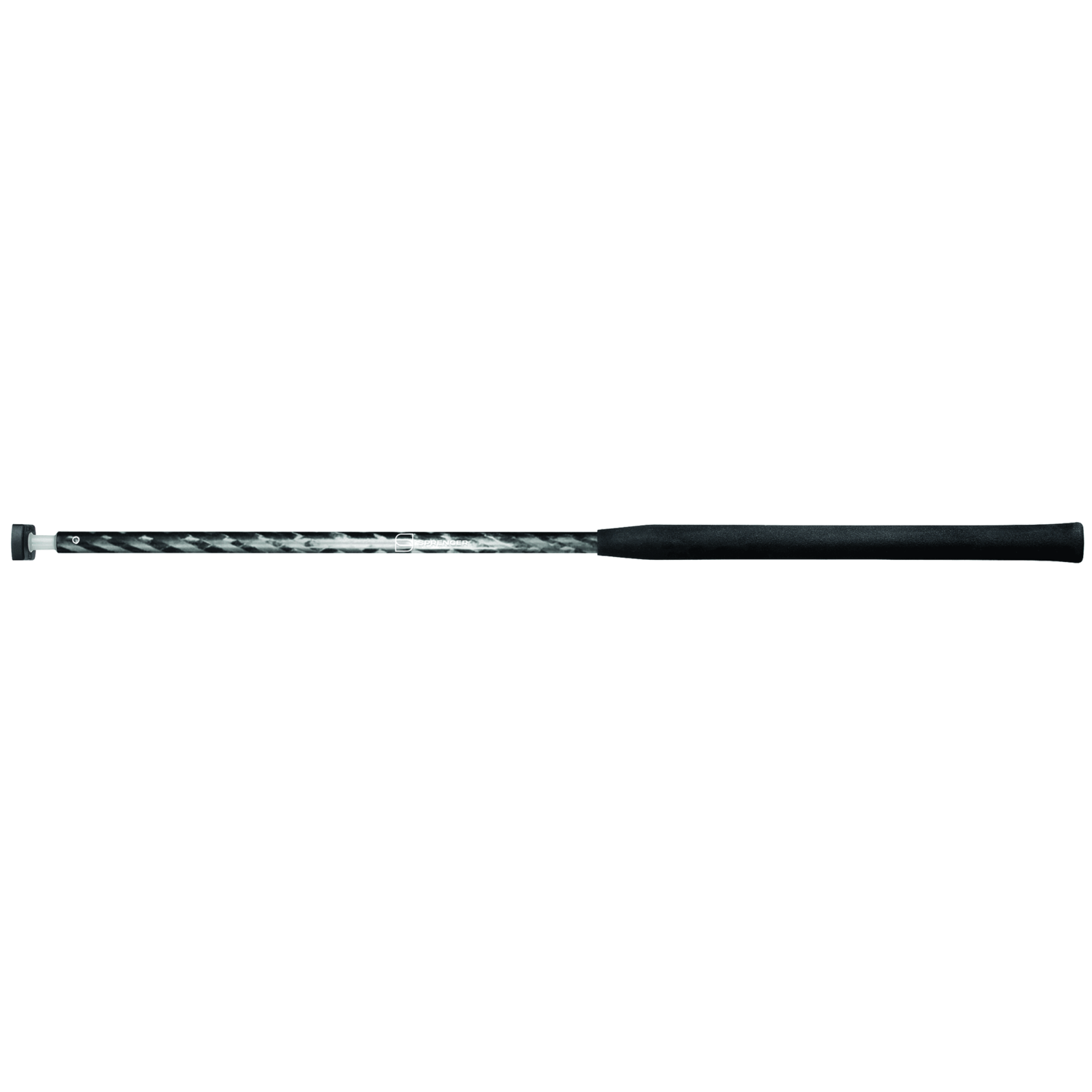

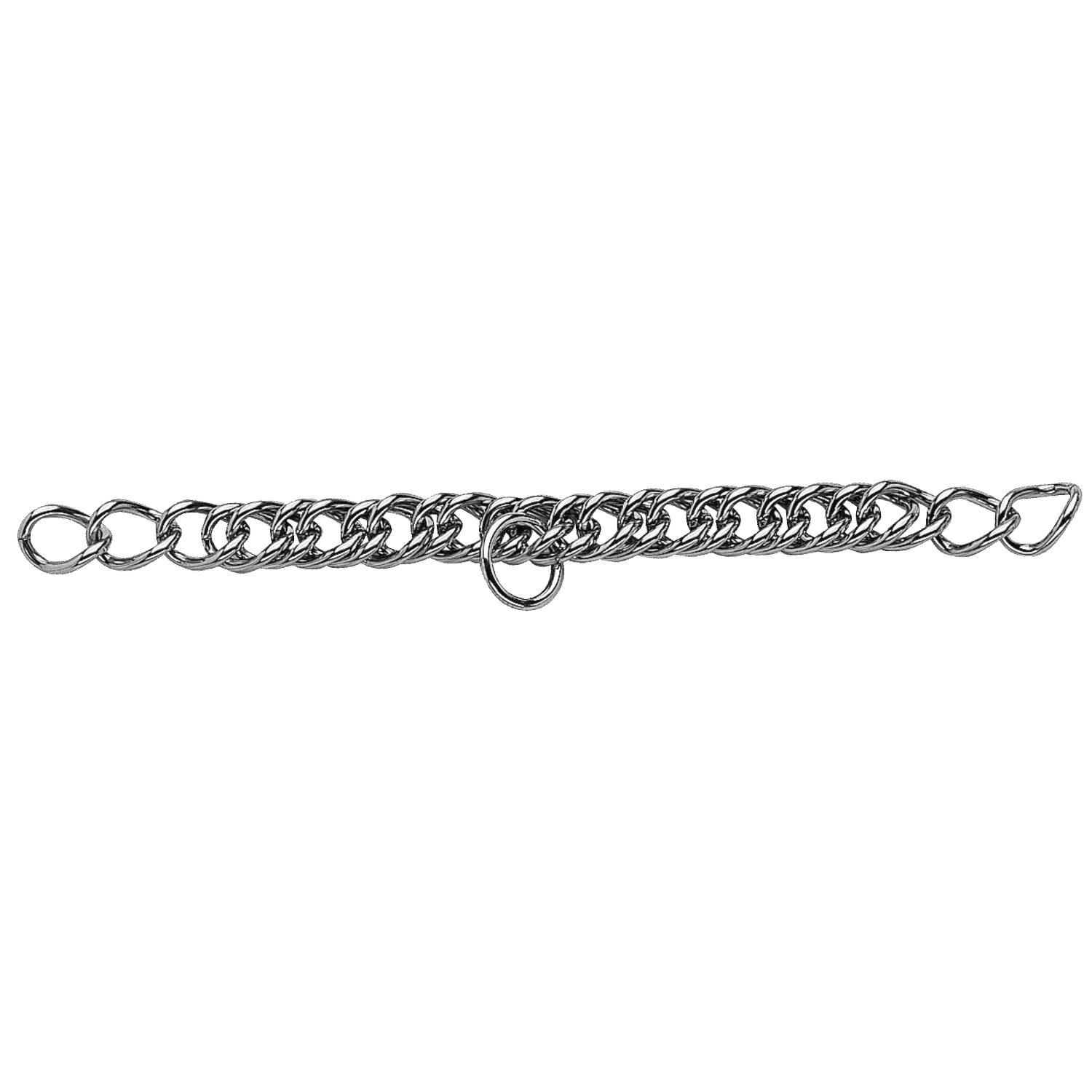

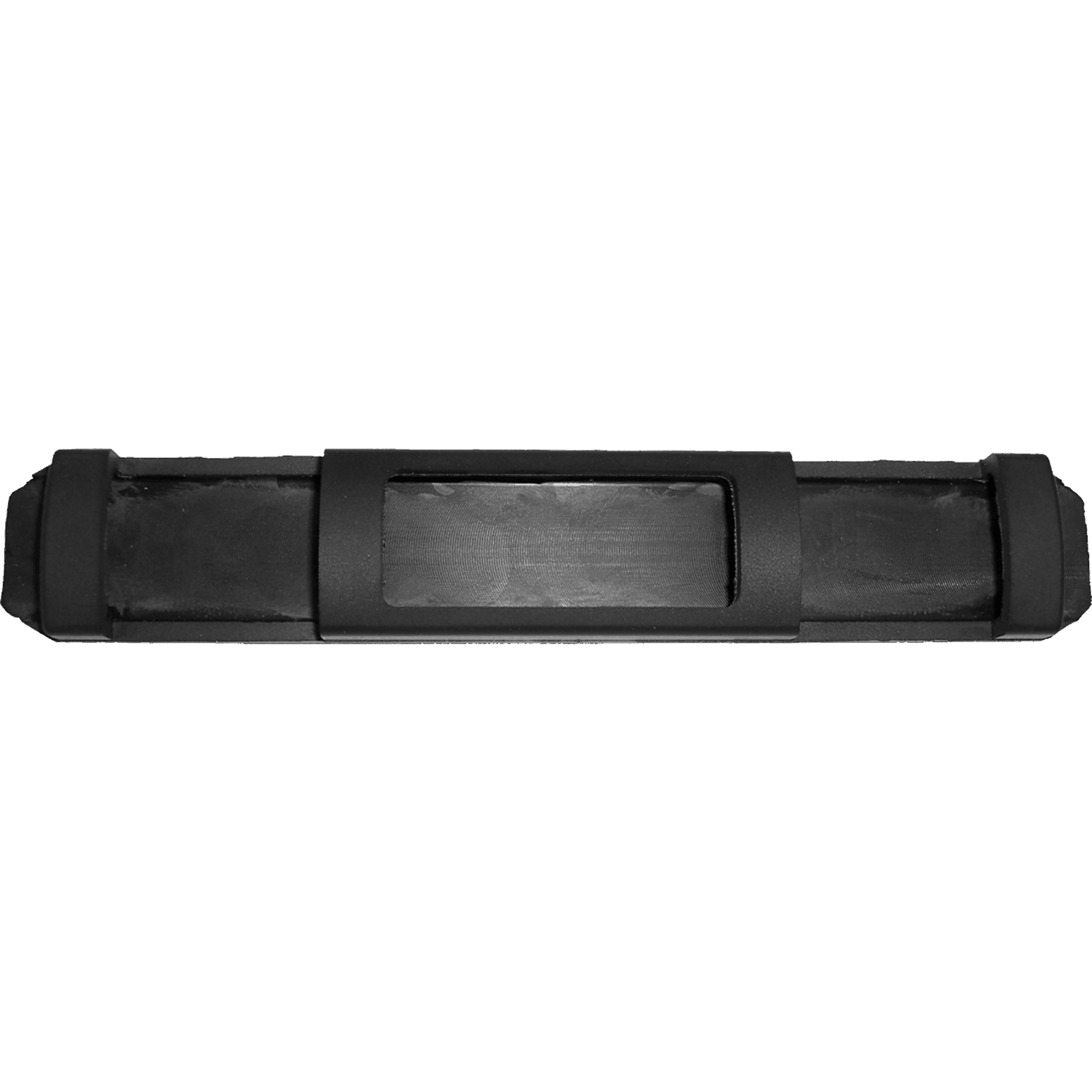

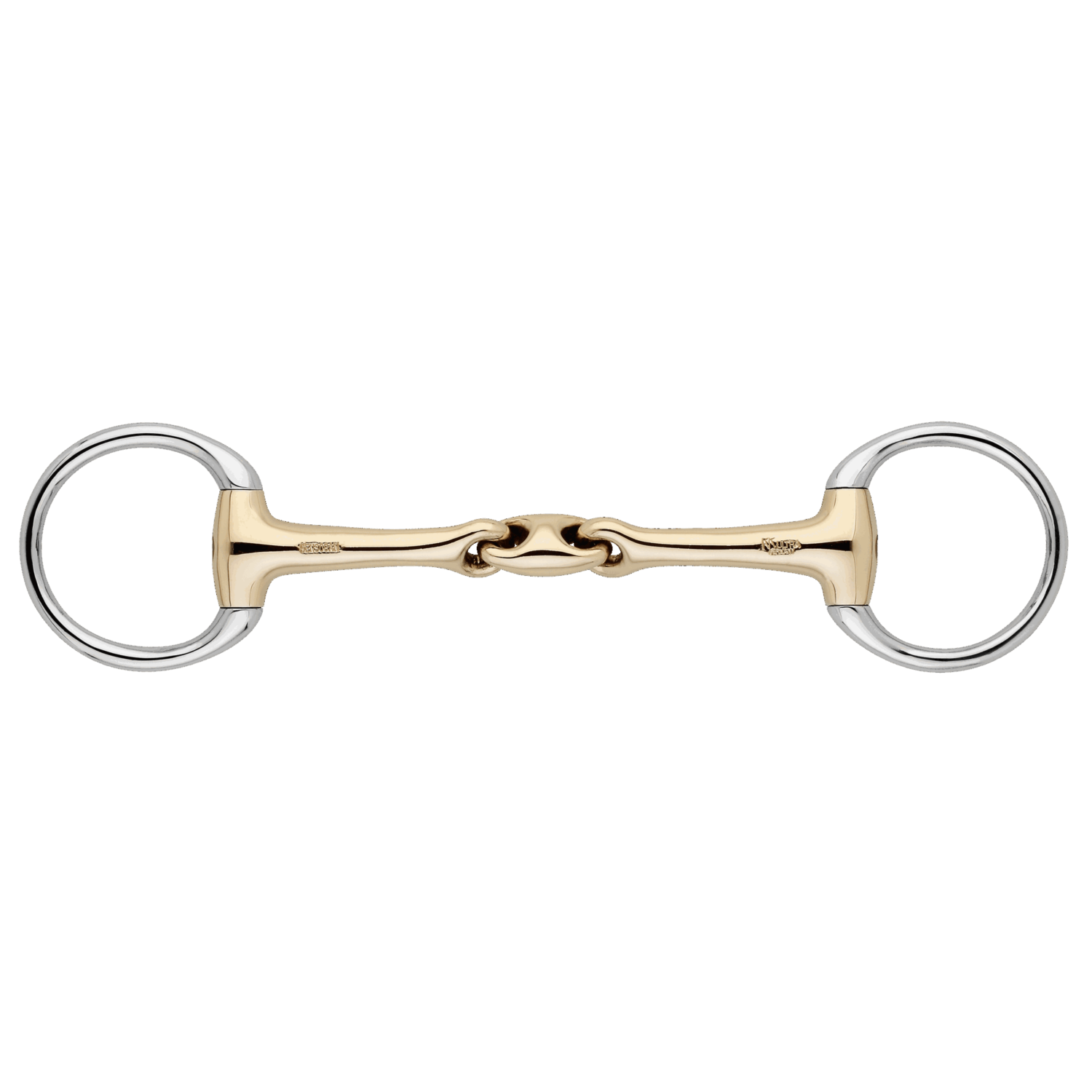

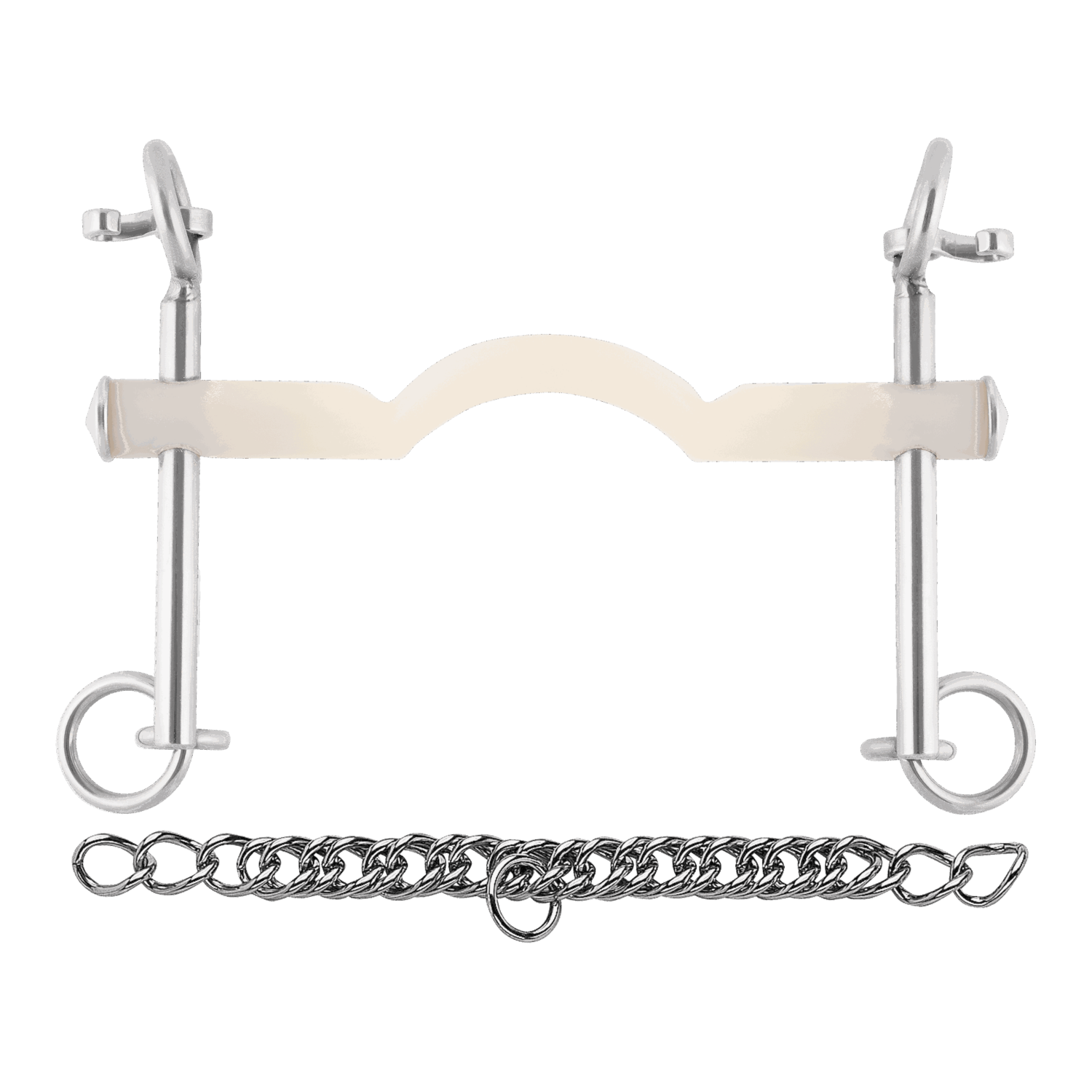

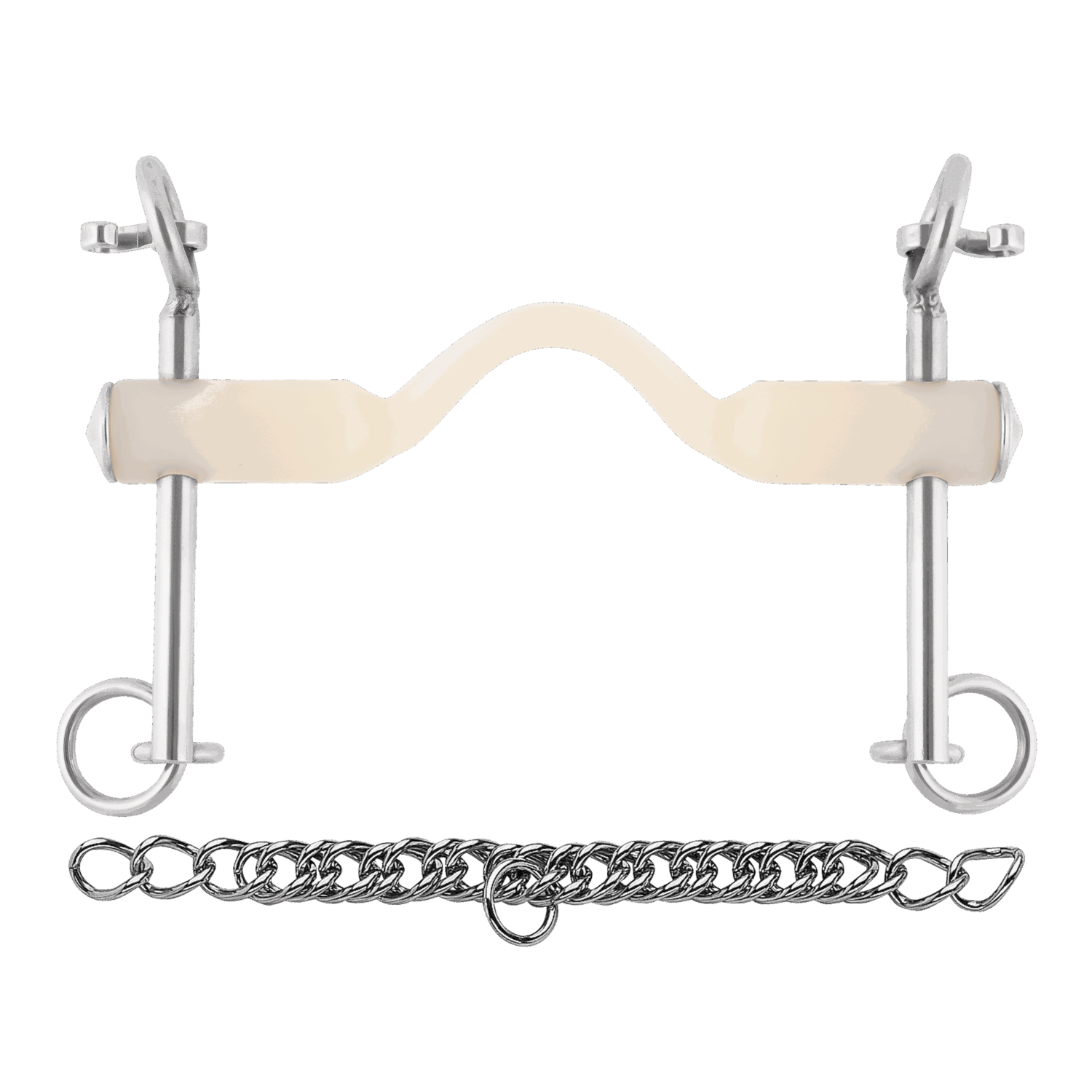

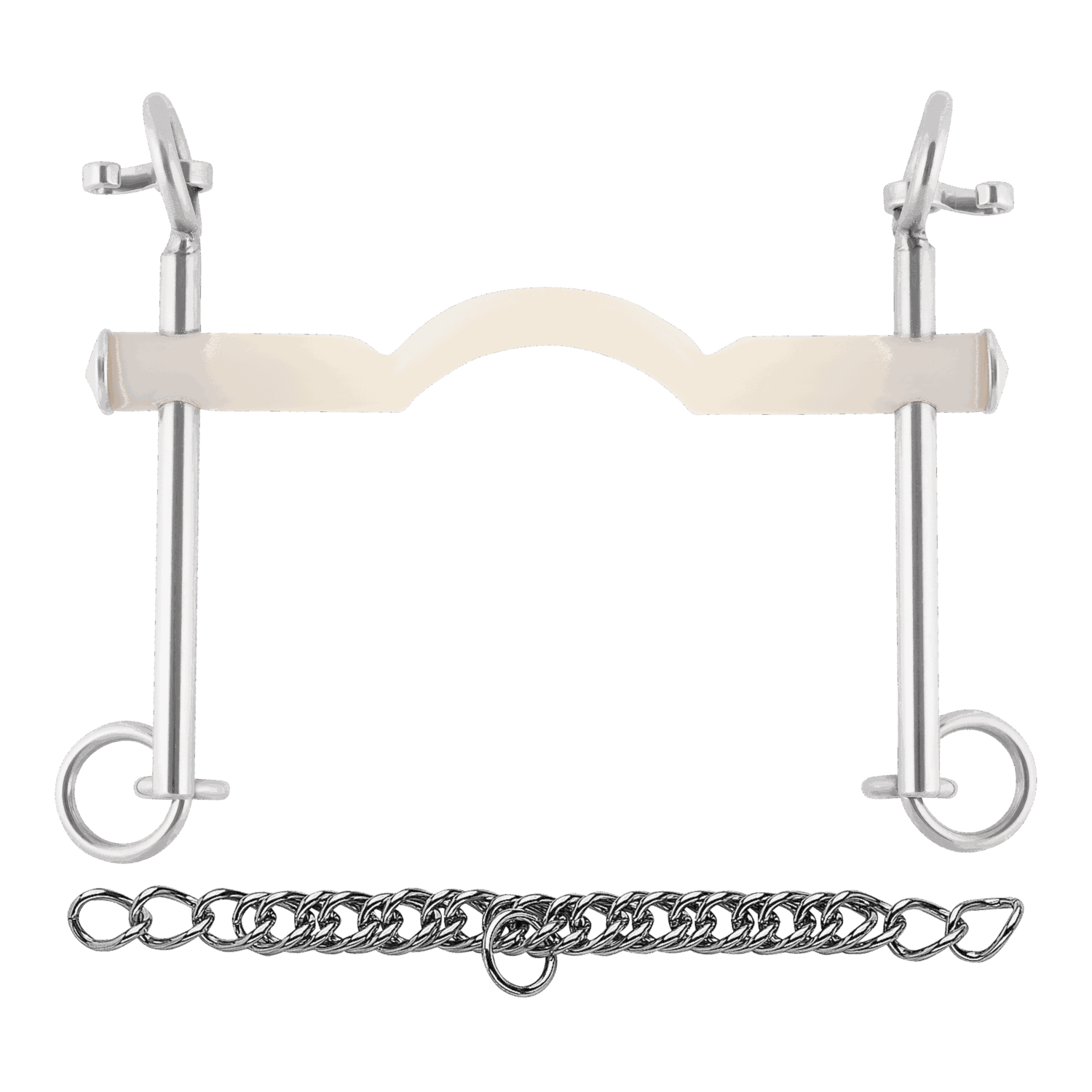

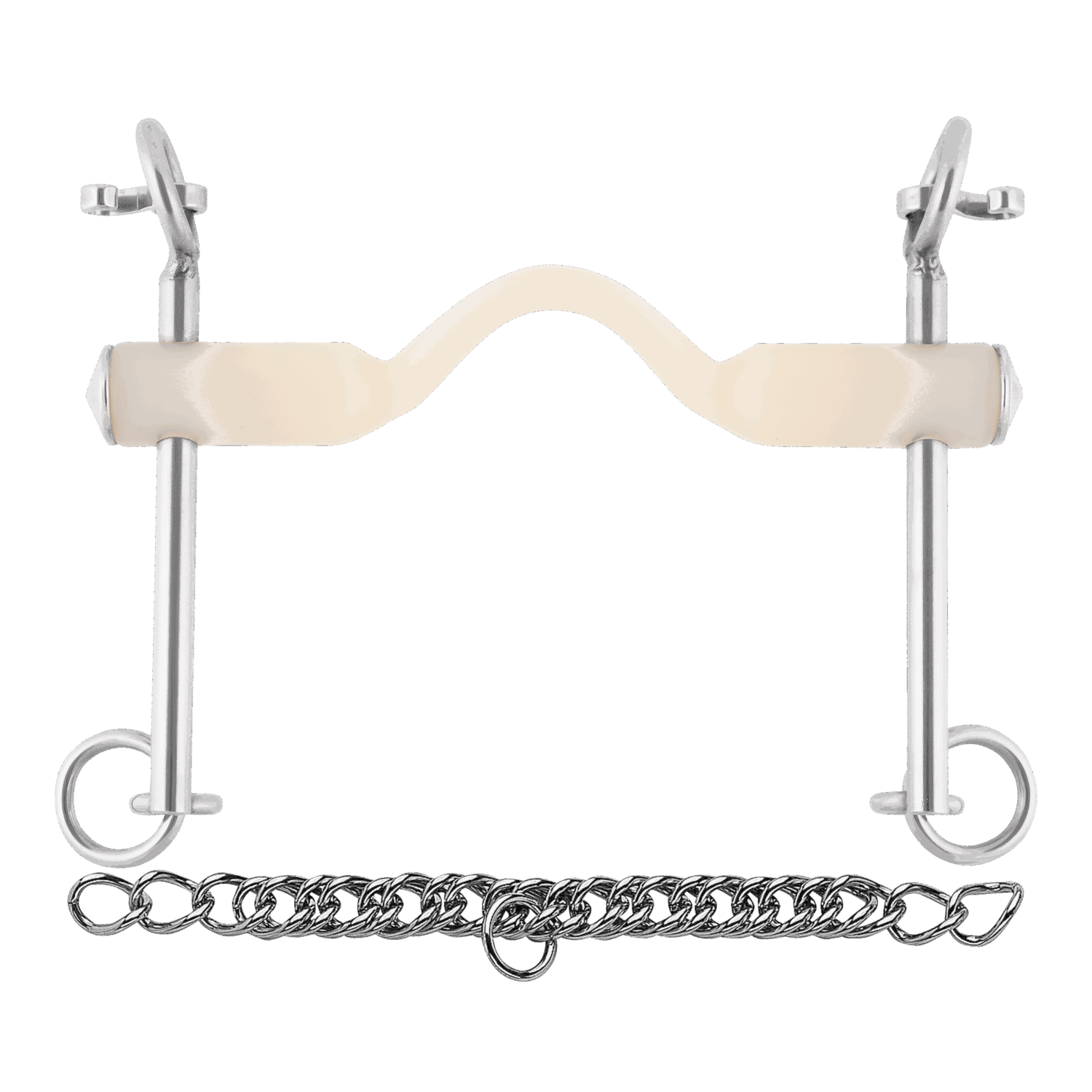

The weymouth is used in addition to the bradoon. It consists of a rigid, mullen mouthpiece and side pieces with an upper and lower shank and a curb chain. The cheek piece of the double bridle is attached to the so-called upper shank (or cheek). The hooks for the curb chain are also attached here. At the lower end of the lower shank are the rings for attaching the curb reins. When the weymouth is accepted, the upper and lower shank rotate around the mouthpiece, creating leverage and applying pressure to the poll.

The ratio between the upper and lower shank, or the length of the lower one, determines the strength of the leverage. The most common lengths of the lower shank are 5 cm and 7 cm. A shorter lower shank, also called a baby weymouth, reacts more quickly, but has less leverage on the poll than a longer lower shank.

The curb chain is hooked into the curb chain hooks. The chain links must be turned correctly and lie with the flat side against the lower jaw. They limit the pressure exerted on the poll. By tightening the curb rein, the cheek rotates until the curb chain begins to engage. Ideally, this happens when the angle between the lower shank and the mouth is between 30 and 45°.

In order for riding on a double bridle to work, it is necessary to take a closer look at the subject and the correct fitting.

One of the biggest and most common misconceptions about the weymouth is the bit width. The phrase "the bit must be larger than the weymouth” is not wrong in principle, but it is misleading! As a result of this misunderstanding, you unfortunately find many riders who ride with bits that are too big and then inevitably fit them too high. This is often the beginning of a cycle in which one problem leads to another.

The correct thing to do is to use a bit that has the same width and shape as the snaffle bit that is normally used. The bit should also be fitted in the same place in the horse's mouth, not higher. The distance to the first molar in the lower jaw should be at least 1-2 fingers so that the mouthpiece does not touch the tooth when the reins are taken up. In essence, the only difference between a bradoon and your everyday snaffle is the smaller ring size and less thickness (standard 12-14mm).

The weymouth lies a little further down in the horse's mouth, where it is narrower, which is why the weymouth should usually be chosen 0.5 to 1 cm smaller than the bradoon. The sides of the weymouth should lie close to the corners of the mouth without pinching them. If there is too much space between the corners of the mouth and the side pieces, the weymouth can slip or tilt.

The thickness of the bit depends on the space available in the horse's mouth. For small mouths, the bits should never be thicker than 16 mm. In Germany, the average bit used is a combination of a 14 mm thick bradoon and a 16 mm thick weymouth. For delicate and small mouths, it is advisable to choose a 14 mm weymouth as well.

The biggest challenge when fitting a double bridle is to assess the space available in the horse's mouth. This is because there must be room for two bits, which must not touch each other when the reins are taken up. The area between the molars and the canines (if any) is decisive for this. But the horse's mouth gap can also have an influence here. Basically, the shorter the distance between the lower and upper teeth and the shorter the mouth gap, the more conscientiously the bits have to be fitted.

If the misunderstanding described above occurs, i.e. the weymouth is chosen in the same size as the snaffle, and the bradoon is chosen one size up, correct fitting becomes almost impossible.

If the snaffle is too big or the distance between the bits is too small, the mouthpiece of the snaffle can slip under or over the weymouth and press into the horse's tongue or sensitive palate. This must be avoided at all costs. Known problems that can arise from this are opening / unclenching of the mouth or pulling up / sticking out of the tongue.

If, on the other hand, the right combination of weymouth and bradoon is chosen, your horse will be comfortable and approach the rider's hand with confidence, even with a double bridle.

There are many different types of weymouth bits and bradoons to choose from. If in doubt, you should seek advice from a specialist dealer or directly from the manufacturer (Link zum Kontaktformular Gebissberatung). This article is intended to offer at least one possible solution to the most common problems. More detailed information on the various types of mouthpieces can be found in out post 'How Do I Fing the Right Bit?'.

When choosing the shape of the weymouth and bradoon, one should also consider the anatomical conditions in the horse's mouth. Difficult cases usually have one of the problems described above: a short mouth gap and/or little space to the canine/molar. In these cases, the two bits lie relatively close to each other and it is important to avoid them touching. Basically, we have to choose bits that save space. Ideal for this are weymouths with a slightly curved bar or higher port that are inclined forward. In contrast to a straight bar, these weymouths create significantly more space for the bradoon. Anatomically shaped bradoons are also more "space-saving" in the direction of the weymouth than straight shaped mouthpieces.

Horses with a fleshy tongue or who don't like pressure on the tongue are often more content with a weymouth with a higher and wider port, e.g. the Bemelmans Weymouth.

For stronger horses, a straighter bar can help them push off the bit better and make the connection a little easier. Here, too, there are versions with different degrees of the port for different thicknesses of tongue.

PART OF YOUR PASSION.